10 years with Miranda July

When doing nothing leads to something

“All I ever wanted to know is how other people are making it through life – where do they put their body, hour by hour, and how they cope inside of it.” – Miranda July, It Chooses You, p. 157

I was walking through downtown Mexico City and putting pillows in broken window frames, wrote visual artist Francis Alÿs in 1990 about his work Placing Pillows. Mexico City was just a few years after the devastating earthquake and its city center was still deeply wounded. Against the backdrop of the devastating political situation that followed the earthquake, Alÿs responded to the urban space with this subtle but precise gesture.

This “sculptural situation” was one of the first to fundamentally frame his relationship to public space and its poetics / politics. But also, to something that extends along Alÿs’s work: a certain Sisyphean task that consciously glorifies the process itself. The process that opens up a time of increasingly rare nature to us: (seemingly) futile activity, paradoxical time, time of mere being.

Subsequently, in 1997, the artist created the first performance of the series called Paradox of Praxis (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing). With the typical Alÿsian unforced poetics, which is also present in his most political works, he pushed a huge block of ice through the streets of Mexico City, until it melted. As time went on, the object disappeared, something became nothing through a great physical exertion.

Alÿs continued to develop these paradoxes in his work, for example in the event called When Faith Moves Mountains in Lima in 2002. It involved a painfully slow movement of a half-kilometer long sand dune. Five hundred volunteers with shovels moved the dune ten centimeters. This action, through a radical gesture (“maximum effort, minimum result”), responded to the then political transition in Peru, but in a broader sense, rhetorically flipped the principle of economic efficiency that forms the core of modern society through a physical metaphor.

We all are familiar with the moments when a lot of effort leads to nothing. However, the fleeting and absurd monumentality into which Alÿs transforms this feeling opens up (even today) new thinking about the process of creation and life itself, about gestures and situations that help us protect our time from being sucked into an insatiable vortex of productivity.

(Source: Galerie Peter Kilchmann)

When I tried to remember the first time I heard about Miranda July for the sake of this text, I recall a scene that is strangely real, even though I know I have never actually met the artist in person. I see Miranda on a plane going to the toilet to wash sweaty spots under her armpits, but in the end, when trying to save a tricky situation, she soaks her entire skirt and returns to her seat, embarrassed, and there she continues in a slightly embarrassing conversation with her fellow passenger, an elderly and famous man. This memory is strange – my brain absorbed it as if I had really experienced the situation, flying from Los Angeles to New York with a view of Miranda July across the alley. I think this memory sediment of mine says a lot about the work of Miranda July herself – how close she lets us, how we find ourselves with her in moments that are painfully familiar in their specific embarrassment, cruelty, vulnerability… and we are immediately seduced by her solitary humor and very specific self-irony. Google finally – through “miranda july wet armpits” search – helped me anchor my surreal memory. I first met July in her short story Roy Spivey, published in the New Yorker in June 2007. It is possible that I encountered it quite by accident, and only because of the illustrative photograph by William Egglestone that I love.

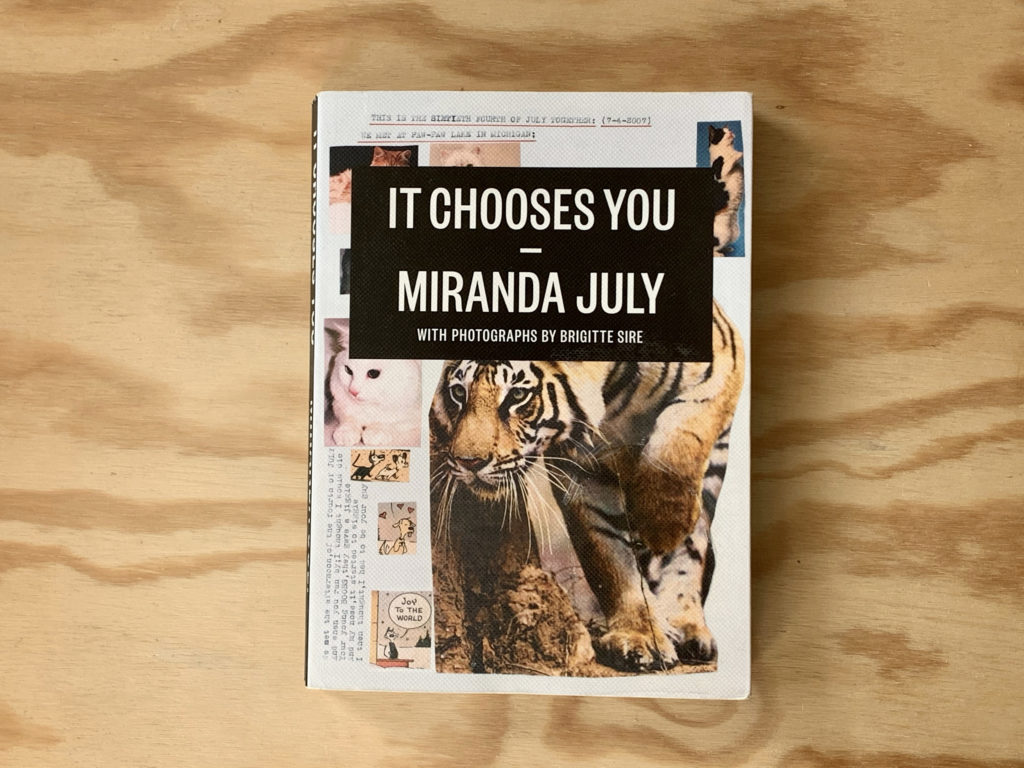

Miranda July and her unmistakable look and style, which over the last decade has gained on the sophisticated strangeness, indie-star, quirky muse. Her first book, IT CHOOSES YOU, which came out almost exactly ten years ago, became my first full-blooded contact with this American filmmaker, artist and writer. If we changed the paradox of the aforementioned Alÿs series just a little – to Sometimes Doing Nothing Leads to Something – it could also be the name of this project.

After winning a Sundance Festival workshop, Miranda July made her film debut in 2005 with her first feature film, Me and You and Everyone We Know. The film won The Caméra d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, a special jury award at Sundance and more. It can be said that the book IT CHOOSES YOU was created as a “sprout” from the time that July went through after this triumph. The great success of the debut, whether it is a book or a film, is not only encouraging for almost every young creator, but with the expectations it brings, it can be extremely paralyzing.

I worked on my screenplay at the kitchen table, or in my old bed with its thrift-store sheets. Or, as anyone who has tried to write anything recently knows, these are the places where I set the stage for writing but instead looked things up online. Some of this could be justified because one of the characters in my screenplay was also trying to make something, a dance, but instead of dancing she looked up dances on YouTube. So, in a way this procrastination was research. As if I didn’t already know how it felt: like watching myself drift out to sea, too captivated by the waves to call for help. I was jealous of older writers who had gotten more of a toehold on their discipline before the web came. I had gotten to write only one script and one book before this happened, writes Miranda July in the beginning of the book IT CHOOSES YOU. We learn that she is desperately trying to finish the script of her second film, The Future, that it is almost finished but from the real conclusion separated by a small but in some way insurmountable distance. However, her paralysis is a bit odd. She knows the beginning and end of the script, but she still has to come up with a compelling middle of the story. And so he just scrolls – scrolls – scrolls, searching for one thing after another. In bright moments, she is convinced that she has found it, the perfect middle of the story, and then she sends draft scripts to the people she cares about. However, these emails are frantically followed by other with the subject “Do not read the draft I sent !! I’ll send a new one soon!” And that’s happening until the time slowly bites away her belief that the script will ever be finished.

In addition to all this, however, she fully and somewhat thoroughly develops various modes of procrastination. She googles her own name, “as if the answer to my problem was secretly encoded in a blog about how unbearable I am.” Despite her hitherto non-existent relationship with alcohol, she begins to drink wine when she returns home, vigorously performs household chores and finds a new hobby – cooking complicated meals.

And besides, she’s looking forward to Tuesday every week, when PennySaver, a Los Angeles-based advertising newspaper, lands in her mail. July writes about how she always starts the newspaper at lunch, and how – since she has no reason to rush to “not writing”, she goes through the ads one by one and finds pleasure in the analysis of individual offers. Not that she wants to buy anything but in a way she is excited by the description of specific things for sale, as if they were miniature newspaper articles. For example, a leather jacket, big and black, that someone thinks is worth 10$. These banal fragments are like little cracks opening the surface of an anonymous life, which appeals to her curiosity. Who is this person? What does he dream about, how does he spend his days? July asks herself, and from this curiosity, which takes the form of a kind of increasingly passionate procrastination, she is gradually getting to a real action. The advertisement for the leather jacket is the crucial one that will open the door to the imaginary other side – by calling the number. With her own imagery, she describes the crucial moment of this short conversation:

There was a pause. I sized up the giant space between the conversation we were having and the place I hoped to go. I leaped.

“Apart from the jacket, I also want to know something about your life. About your hopes and fears “, she blurts out and then asks the owner of the leather jacket for an interview in exchange for a smaller fee.

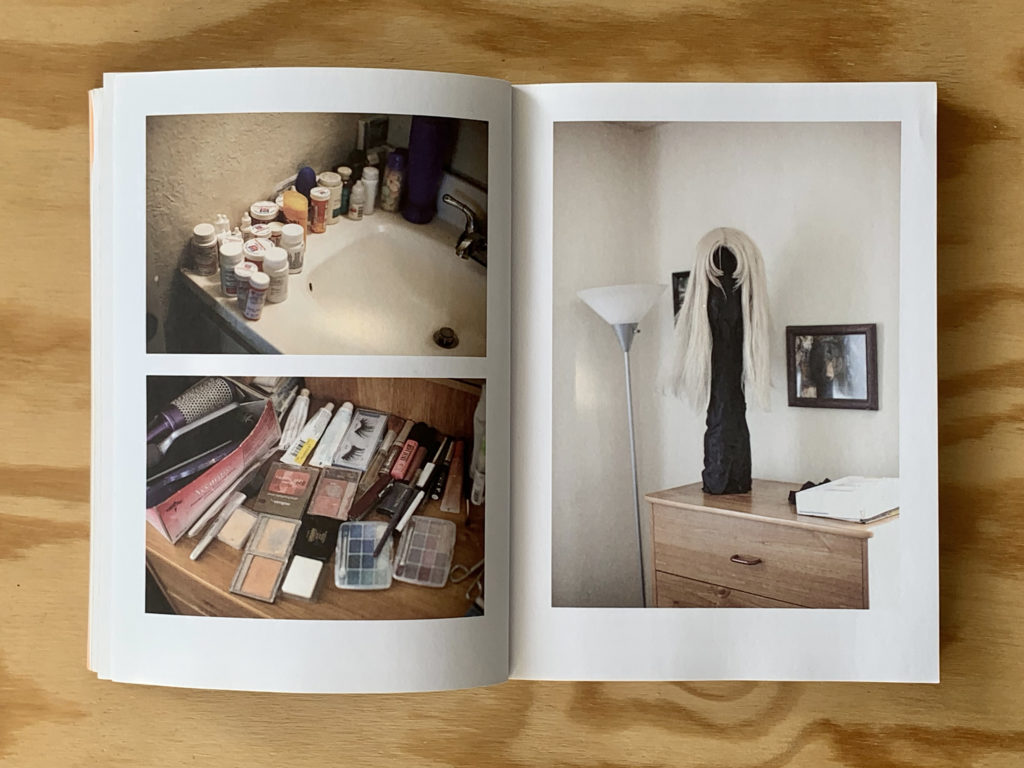

Her journey to Michael is a certain redemption for July, an opportunity to “leave her cave”, the abyss of procrastination in which she is drowning her time. However, the author takes the first PennySaver adventure very seriously, as a real project, equipped with a pocket recorder, in the company of an assistant and the photographer Brigitte Sire. The mundane leather jacket unveils the story of a man who, in his sixties, decided to undergo a transition. From Brigitte Sire’s photo, a man is looking at us in the fragile phase of some “interlude”: the gentle ruffles lining the burgundy T-shirt contrast with his face, an expression that seems harsh, suspicious, maybe a little painful.

From a conversation between July and Michael we learn that he had lived all his life in a body that was foreign to him, and after his first coming out in 1996, he decided to crawl back into the shell. But now he goes fully in, determined to overcome his lifelong fear. The Charm of the Unwanted: Meeting Michael in a strange way, perhaps provocatively, reflects the state of July at the time. His absolute determination and the certain joy that accompanies him and his boldness have a nourishing effect on her, as a necessary inspiration.

July immediately decides to cruise the streets of LA as an “untrained and useless social worker” with a mission to interview other PennySaver advertisers.

Indian sari – Big suitcase – Leopard cub – Photo albums – Hair dryer. Gradually, stories are opened up in front of us – the readers – each of them carries its own intensity, questions, mystery. Open to almost anything, July completely immerses herself in the stories of people that recently took the form of just a few lines in the advertising newspaper. In the book IT CHOOSES YOU, whole worlds, universes, with their own unique texture of being are gradually unpacked for us. And while everyone is completely different, together they act as some psychological geography of LA at a certain time and (social, political) space.

In between meetings with respondents, July talks about the progress of her script. The PennySaver event has moved from the edge to the center of the filmmaker’s life, and the line of work that was supposed to be principal is withering (?) At the edge. “Cumulative despair,” as the author describes. But how can we, as creators, be sure how is this whole thing supposed to be? Isn’t is so that what arises, by chance, on the fringes, is often the most real, powerful art?

PennySaver is still on the table. July reflects the passing of time, which has already connected her strangely with newspaper stories: It seemed Michael had sold the leather jacket; he was ten dollars closer to womanhood. Everything was changing, except me. I was sitting in my little cave, trying to squeeze something out of nothing, she confides in the book.

Trying to squeeze something out of nothing. In fact, it seems quite simple at first glance – the script could not be completed, but in the course of time something else emerged from the process, a new value. In reality, however, the difficult part it is not an absolute despair over a creative crisis, but just staying in this moment long enough and in such openness of mind to show another possible way. A digression that can become the real goal makes sense in a given time and space.

But can every (creative) crisis or block be turned into something meaningful? And is it necessary? The pressure to create values and products from every single part of our being, to extract something from anything – from crisis, privacy, inaction, failure or just being – to name, pack, sell – has become a kind of structure of our time, a neoliberal form, into which we more or less consciously pour it every day. Where has our timelessness gone? Contemplation of leaflets from the supermarket, of drawing on the bottom of a cup of coffee – just like that, without the urge to constantly share something and thus create additional marketable value.

It is interesting to think about Miranda July’s book 10 years after its publication: is the experience of creative crises different than then? Do we even have (a real) time for crises? Would this book be created if it were created here and now? Would July be sitting over an advertising newspaper or scrolling social networks on a smartphone, and what would be different? And how do we get to these people right now – stories that start with an ordinary leather jacket, but invite us into being of those who remain hidden on the periphery?

As early as 2011, July talks about the (ir)relevance of what exists outside the Internet. Obsessively, every PennySaver respondent gets the same question: Do you have a computer at home? Most of them don’t, and that excites her in some way:

As if I feared that the scope of what I could feel and imagine was being quietly limited by the world within a world, the internet. The things outside the web were becoming further from me, and everything inside it seemed piercingly relevant. The blogs of strangers had to be read daily, and people nearby who had no web presence were becoming almost cartoonlike, as if they were missing a dimension.

I therefore consider whether this book is also a kind of time capsule – a document of a certain being in the world, its nature, which is no longer possible. What part of our reality is, ten years after the release of IT CHOOSES YOU, still “out there”?

Author’s note

Procrastination carried out during the writing of this article: Reading my horoscope for the next week, regularly checking the inbox, smelling the Japanese ink lying on my desk. Watering the home flora, eating half a pack of long-stored pumpkin seeds with “white coffee” flavor icing. Constant, obsessive airing of the apartment; googling whether Miranda July is still with her husband.