At the beginning

One of the first things I was asked by the admission committee at the film directing entrance exams was to talk about an interesting female character of world cinema. I remember it as if it were yesterday – in my head I went through all the Bond girls, Hermione, countless girlfriends and mothers and love interests of the film heroes, and Suzanne from the Slovak classic The Fountain for Suzanne – in a wet, transparent T-shirt. All of them were so pretty or exceptionally wise (while pretty), and were as a rule the only women in otherwise all-male ensembles. On the committee there was only one woman, and all of the films in the entrance test were made by men. And so it began to seem a little suspicious that the female characters are somehow all too often found wet in fountains.

The question itself suggested that not only in world history, but also in the history of cinema, the male character is considered standard while the female character is an alternative, an addition , something extra you can ask a fun quiz question about. Not only male storytellers but also male directors, cameramen or presidents are considered to be the standard; standardized as the male story, opinion, world view. The female characters, female directors and female camera operators are a minority – which understandably influenced the content of films, the atmosphere on film sets and the world we live in.

The general lack of female characters (and their diversity) is closely related to who is on the other side of the camera. In the absence of a female perspectives in the writing and production, the authentic depiction of the female experience is under-represented. In this vicious circle, however, the women behind the camera remain missing as many have become accustomed to being reduced to girlfriends, wives and decorations – not to mention that in many film crews women are still treated like props. Our self-reflection is often based on male gaze objectification of our roles and skills – as seen in the history (and the present) of cinema and statistics.

The occasional appearance of a strong female character was supposed to be that hopeful swallow that makes the summer. But at the interview, instead of picking Karenina I fished out some feminist theory on how the vast majority of films are aimed at a male viewer and made by a male author (little did I know I was retelling Laura Mulvey’s Visual pleasure and narrative cinema) and I got the defensive response that I have most probably not seen enough films and read enough books. Or had I just not seen enough female admission committees and female film crews?

The status quo of male dominance continues based on history, gender stereotypes, lack of female role models, behind-the-scenes sexism, power and decision making imbalance, stereotyping and invisibility of women. The four main areas of the problem intertwine and perpetuate each other (diagram below the article). Hollywood, power, capitalism, opportunities.

- Insufficient or stereotypical representation of female roles in film and television (past and present)

- Lack of (visibility of) women in the industry (in the credits, scripts and award nominations)

- Not enough female role models to identify with (fictional and real, see 2)

- Sexism

Boys! Boys everywhere!

In Bitches, Bimbos and Ballbreakers: The Guerrilla Girls’ Illustrated Guide to Female Stereotypes, the feminist collective Guerrilla Girls lists the different types of female characters and labels given to women based on the influence of film and television. Guerrilla Girls is a group of anonymous activists founded in New York in 1985 pointing out sexism and the underrepresentation of female authors and artists throughout the whole cultural spectrum through guerrilla campaigns. Probably the best-known of their posters addresses the underrepresentation of women in arts with the slogan “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female”. There are incomparably fewer female artists being exhibited compared to male artists – despite the fact that 95% of people involved in fine arts are probably not men and female art graduates and students account for way more than 5%.

The same applies to the film industry. Statistics show that the problem of representation does not stem from the lack of female professionals but from the lack of opportunities and willingness of the producers and from how the (patriarchal) system is built. This could be illustrated by the example of New York’s famous Tisch School of the Arts, where 50% of film directing graduates are women. Then we can have a look at the current Oscars and Cannes awards and see for ourselves that unequal opportunities are not a problem of the past.

In Slovakia the topic is approached with a so-called gender-blind attitude combined with open sexism. While television is packed with sexist jokes and objectification of women, gender blindness teaches us not to see that there are more male characters on the screen and more male professionals visible in the industry. We pretend that in an equal world having only men everywhere is not a problem (after all, gender does not matter!), but by accepting this we only accept the notion that men are “naturally more competent”.

Somewhere between gender blindness and the invisibility of women on the screen and behind the camera lies the problem of language. Slovak (as many other languages) is gendered and mostly uses the generic masculine form – so that to describe a mixed group of people or professionals (even if it’s 99 women and one man) the masculine version is used by default. This can be altered by using gender sensitive language and the double form (such as “actors and actresses”) but thanks to the above mentioned gender blindness this is opted for rather rarely. The fact that film directing study scripts uncompromisingly use gender-insensitive language and repeatedly refer to a male director as the standard version of the job only perpetuates the perception that what is neutral is, in fact, masculine. The use of a gender-balanced language would illuminate the fact that women also exist, create and make decisions in this and other fields.

In her essay Female philosophy? Philosophy from a female perspective? the Slovak philosopher Etela Farkašová examines the problem: “Language and ways and methods of cognition always include a certain background, which is more or less determined by gender – an aspect that is not taken into account by traditional philosophy. One of the consequences of this disregard for the gender was the ‘false universalization’ of a character – that was expressed in language. […] In Western culture, a man is understood as universal being, considered general, normative and a woman is defined negatively, i.e. identified as ‘non-male’. Similarly, the logic of Western discourse is largely based on unification of a gender-neutral human with a man – while a woman is understood as either something absent or something that also identifies with the universal subject: she can either remain silent or adapt to the established universal (but essentially male) discourse.”

In film, a man is still considered to be the universal character, the mover of the plot, the one the viewer is to identify with. The trope Men Are Generic, Women Are Special, or the “Smurfette principle” are recognized. The term “Smurfette Principle” was coined by Katha Pollitt of The New York Times when she described the trope of one (often stereotyped) female character among many men – like one Julia Roberts in the Ocean’s Eleven man-pack. It shows that men are the norm and women are mere variations; men are central, women are marginal; men are individual and women are typified. Men are those who define a group, its story and its value codes. A woman only exists in relation to men. Her only role, mission, possibility and reason for existence is to be a woman, a man’s complement confirming the universality of a male story.

The famous essay by the film theorist and feminist Laura Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1975), criticizes the projection of the patriarchal organization of the world in the film tradition in which man is the person who is looking (subject) and woman is the one exposed (object). In her conception, she draws from psychoanalysis and emphasizes Freud’s concept of pleasure of watching (scopophilia), in which the man participates actively and the woman passively. She coins the term “male gaze” and points out how it is repeated in film–a man behind the camera, a male viewer and a male actor–and makes a particularly important contribution to film and feminist theory with the observation that film is not neutral. Through its nature film works with gender imbalance directly – it is made by men and for men, mediating the male experience and the male view of the world, of female character and of the female body.

According to Mulvey, watching a film yields pleasure for the (male) viewer by looking at an active male and a passive female character. Women are in the traditional exhibitionist role – watched by the eye of the cameraman/director, male actor and male viewer, while their appearance is designed to enhance the visual and erotic effect. Women in the movies are there to be looked at (to-be-looked-at-ness).

Mulvey analyzes the way a woman is looked at by through the combined view of the male viewer and a male character: “The exposed woman traditionally exists on two levels: as an erotic object for the characters within the story and as an erotic object for the viewer in the audience, while the tension between these gazes moves between both sides of the screen. The woman appears in the story, and the viewer perspective is skillfully combined with the one of the male characters in the film without compromising the credibility of the story. ”

Even more creepy than realizing that the film is, in its structural nature, a male fantasy, is Mulvey’s reflection on Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of the fear of castration that a woman represents. The image of “woman” is adversarial – it combines attraction and seductiveness, but at the same time provokes anxiety about castration. Its presence and appearance remind the male subject of the absence of a penis, and therefore the female character is the source of various other deep fears. The woman has to be “punished” or “solved”, which has been done in two ways: through narrative structure and through fetishism. According to Mulvey, a woman is automatically “guilty” in any narrative structure, which can be solved either by punishment or by redemption through marriage, the traditional ends of female characters in movies. Either she must die, or she must wed. Mulvey explores these conclusions through Alfred Hitchcock’s work, claims that film requires sadism and considers it a male dominated art form. At the same time, she reminds us that what is essential is WHO is watching and WHO is telling the story.

Everybody’s stories for everybody. But can everybody be a woman?

Mulvey’s essay was written in 1975 and is still accurate on many levels as today’s research and statistics unveil similar problems in contemporary cinematography. Stacy Smith, a Doctor of Social Sciences at the University of California (UCLA) who is a founder of the Media, Diversity and Social Change Initiative, has long been involved in the topic of how film and audiovisual media represent and impact the position of women in our society and how the female characters keep being underrepresented or completely invisible. She is not the only one to claim that we have reached an “epidemic of invisibility of female characters”.

In her research Smith is mainly focused on Hollywood and commercially successful films, but her conclusions are easily applicable to indie films or art house cinema in Europe. Throughout all the observations and data we should not forget the connection between the way women are portrayed and the low percentage of female directors and professionals behind the camera.

“Women are still significantly absent on screen. Across 800 movies and 35,205 speaking characters, less than a third of all roles go to girls and women […] If we lived in the screen world, we would have a population crisis on our hands.”

“There are two main reasons for the invisibility of female characters. Firstly, the gender identity of those who create the content, and secondly, the misunderstanding of what viewers are watching movies. If you want to change these patterns, all you have to do is employ female directors. It has been shown that female directors have been associated – particularly in independent and short films – with more women and girls on screen, more stories about women, more stories about women over 40 years old. ”

The more female authors and directors come into play, the better the female perspectives and characters are represented on the screen. Smith also looked at the subject of age – confirming that female characters of middle or older age are hugely absent. She also affirmed (as Laura Mulvey in her essay 45 years ago) that women are more sexualized on screen than their male counterparts. There is a three times greater chance that female characters will be displayed half-naked and impossibly thin.

Comedian Amy Schumer works with this topic systematically. In her sketch The Last F * able Day the actresses Patricia Arquette, Julia Louis-Dreyfus and the screenwriter and actress Tina Fey celebrate Julia’s 50th birthday calling it “the last day someone wants to sleep with you”. They describe the absurd reality of how older women fall out of Hollywood movies because of their age and allegedly “declining attractiveness”. The casting experience of actress Maggie Gyllenhaal says it all: “I am 37 years old and I was told I was too old to play a lover of a 55-year-old man.”

When considering the female experience and perspective an opposition to the male perspective (through which we are accustomed to look at stories by default) it is very important to realize WHO is talking. If experience is provided only through a male prism, a lot remains invisible. The male experience is not omnipresent and offering stories through their optics is not enough – even if they tell stories of women or a queer heroes and heroines. Telling someone else’s stories for them instead of giving others a word – passing the mic – is not a solution.

i-D magazine has recently published a text on the issue of authorship and representation of underrepresented characters in queer literature for youth, mostly written by heterosexual female authors. It might seem that it does not matter WHO writes it, but the point of view and the experience of the author is notable – especially for the readers of the target group. Queer writer Adam Sass commented on Helen Dunbar’s new book about a teenage queer boy, taking place during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. “As well researched the book may be and as wonderful a writer as Helene is (…) When you’re not part of an own voices community and you’re writing about that community as a guest in that space, you really have to be looking out for your blind spots and asking yourself the questions: Can you write about this? Absolutely. But should you?”

One hundred years

In September 2017, the British Film Institute published research findings that 31% of the actors in films before 104 (!) years were women, while in 2017 women accounted for 30% of the characters on screen. The analysis covered more than 10,000 films and 250,000 people who worked on them, either in crews or acting positions. It turned out that only less than 1% of the films made between 1913 and 2017 had the majority of female staff. Between 2000 and 2017 it was just around 7% of films, while only 4.5% was directed by a woman. It is no longer just about how there’s too many male characters – there are (way) too many male staff members, too. Not to mention the unbalanced financial evaluation and sexism that women are confronted with in many various working environments.

Statistics are unrelenting – a recent report by British producer and screenwriter Stephen Follows, in which he also looked at the gender of employees in other positions than actor/actress and male/female directors, had shown that 75% of the most commercially successful films are directed by men. In his conclusions, there is a clear gender difference between the different sectors of the film industry – women being mostly employed in costume and set design departments or in casting directing. On other hand, the visual effects employ only 17.5% of women, music only 16% and the camera and lightning departments win the “NO WOMEN competition” with the beautiful result of being 95% dominated by men.

The good news is that in the US, the American Civil Liberties Union in cooperation with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has already filed a proposal to investigate these almost absurd numbers. Eurimage has also recently responded to the current situation with its new program to balance the number of women and men in the industry at 50:50 by 2020.

Accuracy tests

The lack of female characters and their flattening is reflected in the well-known Bechdel test, invented by Allison Bechdel in her comic book Dykes to Watch Out For (1985). Bechdel tried to devise a relevant and simple way to point out gender inequality in fiction and came up with three basic questions/rules to reveal just how much a film, a book, a play or a comic considers its female characters relevant. The questions are: Are there at least two female characters with a name in this film? Do they have any dialogue in at least one scene? If so, are they talking about something other than men? Bechdel’s test is only passed if the answers to all the three questions are positive.

Perhaps it is not surprising that most of the films do not pass, which shows just how much the authors care about the female perspective and the complexity of female characters. Of course, the test is not the most reliable and unambiguous measure of the female representation and feminism of the film, although Eurimage has started to use it as a precondition for funding new film projects in 2014 in order to achieve gender equality. However, many films will succeed in Bechdel’s test only thanks to banal conversations between female characters – it is enough if they give each other a compliment, or exchange two sentences about cooking, baking or new makeup.

In various bloggers’ communities online there are other tests trying to legitimately assess the representation of women in film. In addition to the Sexy Lamp Test that jokingly swaps the female character with a lamp in order to test whether the story changes then, the principle of the Mako Mori test has also became popular. It gives the film three different conditions: the film must have at least one female character, this character must have its own plotline, and this plotline should not only serve as a supporting storyline for male characters.

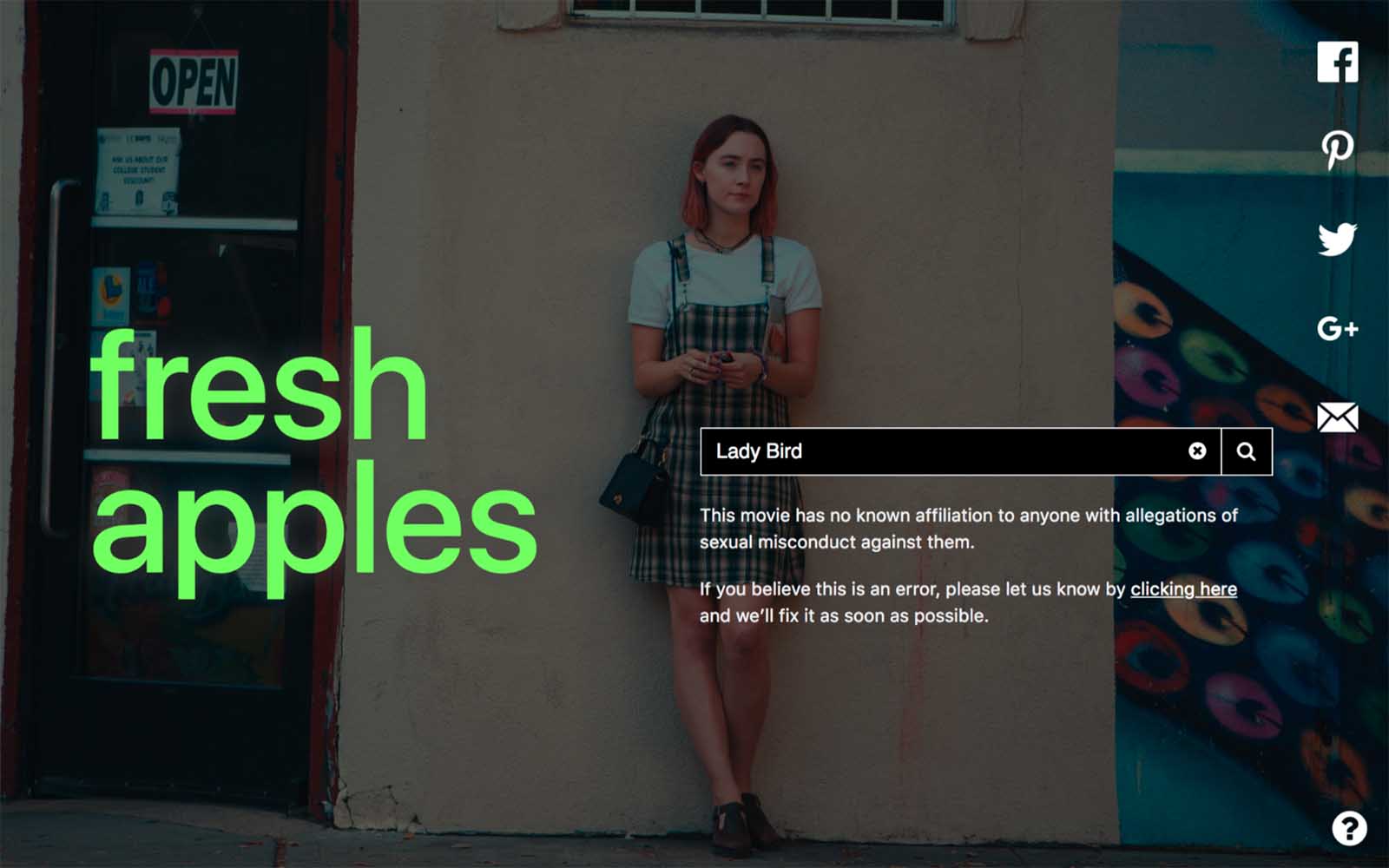

In the light of the #metoo and Time‘s Up campaigns, which focused on another sphere of inequality in the film industry – sexism and harassment of women in the work environment – other ways of assessing the correctness and balance of the film have also emerged on the Internet. The Rotten Apples page is a database that, after entering the name of any movie, evaluates whether the movie is classified as Rotten Apples or Fresh Apples, based on whether any of the filmmakers (producers, actors, directors…) were accused of sexual abuse.

Of course, neither of these tests will precisely evaluate the current state of the cinema, but the mere existence of such tests is important for shining some light on the situation. The Bechdel test is a very simple and entertaining conversational argument on gender inequality at a dinner table after going to the cinema.

One of the last reasons for the non-feminine state of the film industry is harassment. In addition to the dark waters of the “celebrity” scandals and accusations, there is a whole lot of “unnoticed” and common situations that make female work staff disadvantaged. Shit People Say to Women Directors blog is an international database of unpleasant and even violent experiences. These are not the stories of meetings the wealthy predators in hotel rooms, but ordinary diary notes of how impudent or slimy a sound engineer/lightning technician/actor was to the female director/member of production/camera operator just because he refuses to respect a woman on the set.

Katarína Kubošiová, who worked in various television crews as an assistant director, illustrates the situation from Slovakia. In her interview for the newspaper SME she touched the topic of film-set sexism and admitted the well-known fact: “My female friends working in film crews have understood a long time ago that they need to wear baggy boyish clothes to sets to avoid unsolicited butt checking by their male colleagues.”

Let’s imagine…

Can you imagine that not just in one film – but in every film, there would be a vast majority of female characters? That every film shooting would be strictly female staffed, except for one male set designer back there? The unbalanced status persists and the viewers, teachers, artists – we all are responsible. We must look critically at its causes and consequences and constantly question the current state of affairs.

We cannot flip the entire history of cinema, art and humanity inside out, but we can influence the situation with our own work and/or by the careful selection of favorite female filmmakers, programs we watch and recommend, screen and teach. We can decide to not accept the percentage of male professionals sitting in the funding decision making juries claiming that the documentary film about giving birth is a “marginal topic”. We can remember and critically challenge WHO evaluates stuff and what are the criteria. We can not ignore the comment like “women do not understand cameras” or decide to watch the section of films directed by women at a film festival without the absurd grumbling that it is “discriminating men”. And finally, we can consider whether the microscopic number of women who have an Oscar on their shelf indicates that women are just not good enough. Could it all be just that simple?

Bibliography :

CAVARERO, A.: Ansätze zu einer Theorie der Geschlechterdifferenz. In: DTIOTIMA. Der Mensch ist zwei. Wien 1989.

CVIKOVÁ, Jana; JURÁŇOVÁ, Jana: Ružový a modrý svet. Dunajská streda: Aspekt, 2003.

FARKAŠOVÁ, Etela: Filozofia so ženskou tvárou. Bratislava: FIF UK, 1996.

FARKAŠOVÁ, Etela: Štyri pohľad do feministickej filozofie. Bratislava: Archa, 1994.

FILOVÁ, Eva: Eros, sexus, gender v slovenskom filme. Bratislava: SFU, 2013.

GUERRILLA GIRLS: Bitches, bimbos, and ballbreakers, the Guerrilla Girls Illustrated guide to female stereotypes. New York: Penguin, 2003.

HOOKS, Bell: Feminizmus do vrecka: o zanietených politikách. Prvé vydanie. Bratislava: Aspekt, 2013.

KICZKOVÁ, Zuzana: Otázky rodovej identity vo výtvarnom umení, architektúre, filme a literatúre. Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského, 2000.

LE GUIN, Ursula: The Carrier Bag of Fiction, 1985.

MULVEY, Laura: Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen 16, 1975.

https://stephenfollows.com/do-women-prefer-films-made-by-female-filmmakers/

http://www.vulture.com/2018/04/how-50-female-characters-were-described-in-their-screenplays.html

https://www.southampton.ac.uk/news/2016/05/women-film.page